Old Princeton professor Samuel Miller’s version of “Christian nationalism”

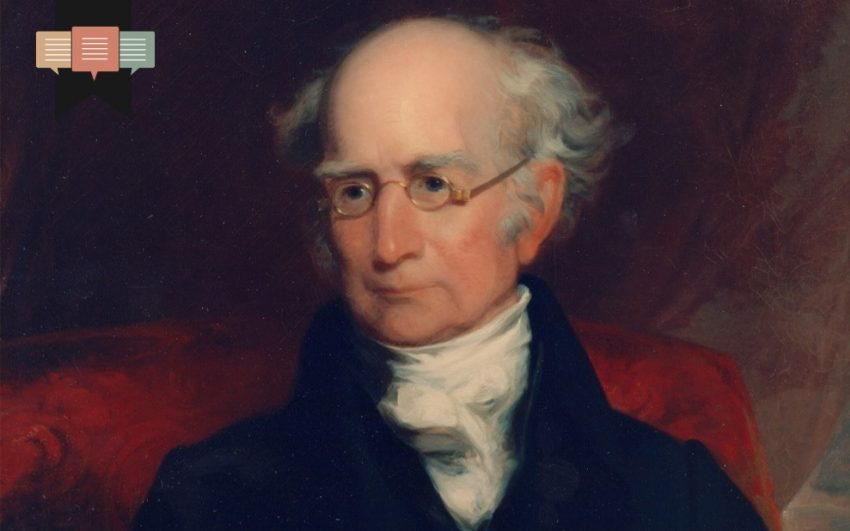

For several months, I’ve been reading a few pages a day during my devotional time from The Pastor: His Call, Character, and Work by faculty and friends of Old Princeton. Banner of Truth published the book last year, and all the addresses are well worth reading. The chapter from Samuel Miller, “Holding Fast the Faithful Word,” is especially striking. Miller was an Old School Presbyterian and was one of the first professors hired at Princeton Theological Seminary in 1813. Miller’s sermon, delivered on Aug. 26, 1829, at the installation of William B. Sprague at Second Presbyterian Church in Albany, N.Y., is a detailed analysis of the importance of sound doctrine. The seventh point, in particular, is worth examining in that it provides a powerful and, dare I say, salutary form of what some might call “Christian nationalism.”

Let me state clearly that I am not jealous to reclaim the term Christian nationalism. In fact, “reclaim” is not even the right word. As I’ve noted before, virtually the only people talking about Christian nationalism are those most steadfastly opposed to it. I’m not looking to defend a term I’ve never been in the habit of using.

What is worth defending, however, is Miller’s vision of “enlightened patriotism.” He begins his seventh point by asserting that “the diffusion of sound religious doctrine through all classes of the community is one of the surest means of establishing and perpetuating our national privileges.” Miller believed America was a land of God-given liberty.

“We often, my Friends, congratulate ourselves on the free constitutions of government under which we are so happy as to live,” Miller wrote. “That our lot is cast in a land where the people, under God, are supreme; where we are not called to bow to the will of a crowned despot, or to the oppressions of privileged orders: where we have no ecclesiastical establishments; but where, under governments of our own choice, and laws of our own formation, all enjoy those equal rights to which the laws of nature, and of nature’s God entitle them. And we may well congratulate ourselves, and be thankful for these privileges. The great Governor of the world hath not dealt so with any other nation.”

The dream was not a Christian takeover of government, but a nation founded on God-given freedom, shaped by Christian values, and filled with Christian teaching.

Of course, we can fault Miller for overlooking the plight of enslaved African Americans when it came to the enjoyment of equal rights. (Princeton recently removed Miller’s name from its main chapel because, although Miller did not like slavery and desired its eventual demise, he sadly owned slaves at one point in his life.) But don’t miss Miller’s larger point: He believed (and knew his audience also believed) that the United States was a nation uniquely blessed by God. The question, then, was how Christians and patriots should pass on those blessings to future generations and how we may “rationally hope that these blessings will be preserved inviolate and transmitted to a distant posterity.”

Although newer voices of “infidel fanaticism” wanted to reject the religion of Christ and throw off the restraints of a religious and moral code, Miller insisted that without sound doctrine, Americans could not truly be moral, and without morality they would be miserable. In making this argument, Miller was not much different from George Washington or John Adams or most of the Founders, who believed that a free people required virtue and that the inculcation of virtue required (some basic version of) the Christian faith. Miller called upon “enlightened patriotism, as well as piety,” to labor unceasingly to impart sound doctrine to all classes of people for the sake of “our beloved country.”

Importantly, Miller’s “enlightened patriotism” did not entail a state church (like Anglicanism in Virginia) or a Presbyterian establishment (like the Scottish Kirk). Every “species of alliance between church and state is forbidden and can never fail to become a curse to both.” Miller did not want an officially Christian nation, but he did hope for a nation that was demonstrably Christian. In fact, he believed sound doctrine was the best medicine for the health of the republic: “You cannot take a more direct and certain course to render the insidious demagogue despised, and to deprive the profligate votary of ambition of all his influence; to inspire a love of liberty, and to promote the prevalence of the purest patriotism.”

Miller’s prescription for America would not have been controversial in Albany, in the Presbyterian church, or in almost anywhere in early 19th-century America. Miller’s evangelical audience was not hoping for a reunion of church and state. At the same time, neither was his audience nervous about a full-throated appreciation for the inestimable blessings of American self-government and constitutional liberties. Miller’s “Christian nationalism”—to use the contested term—was not a political platform as much as it was the widely shared assumption that (1) Christians had good reason to be thankful for America, (2) Christianity has been instrumental in the founding of America, and (3) Christianity had a key role to play in preserving and passing on the privileges that belonged to free Americans.

The dream was not a Christian takeover of government, but a nation founded on God-given freedom, shaped by Christian values, and filled with Christian teaching. “Christians! Ministers of the gospel! Here lies our country’s fairest, best, only hope!” Miller enthused. “To those who love the cause of Christ, is committed, under God, her precious destiny. Spread Christian knowledge in every direction.”

Wasn’t he right?