It’s been said that the most important word in the title Christianity and Liberalism is “and.” With that little word, Machen made the central thesis of his book unmistakable: there is Christianity, and there is liberalism. They are not the same thing. Whether individual liberals might possess saving faith in Christ was not a question Machen presumed he could answer. “But one thing is perfectly plain,” he wrote, “whether or not liberals are Christians, it is at any rate perfectly clear that liberalism is not Christianity.”

If Machen’s “and” seems provocative, it’s worth understanding the context in which his book was published. In February 1920, an ill-conceived plan of union precipitated Machen’s bold disjunction. Representatives from eighteen denominations met in Philadelphia as the “Council on Organic Union of Evangelical Churches in the United States.” The resulting Philadelphia Plan called for the mainline denominations to unite as the United Churches of Christ in America. The 1920 General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA), Machen’s denomination at the time, embraced the plan of union and sent the proposal to the presbyteries for approval. This was Machen’s first General Assembly as a commissioner—he had only been ordained in 1915—and he was astonished by how little the proposal was debated and how quickly it was pushed through the Assembly for a vote. Both Machen and his Princeton Seminary colleague B. B. Warfield strongly opposed the Philadelphia Plan, arguing that the creed on which the union was based contained nothing truly evangelical, let alone distinctly Presbyterian.

Like many pleas for ecclesiastical unity before and since, the 1920 plan was steeped in vague, shallow, and imprecise language. Although it failed to achieve the support of the majority of presbyteries, a line had been crossed. By seeking union with many non-Reformed denominations, and by including Christian traditions as diverse as Methodists, Quakers, and Moravians, the “Philadelphia Plan” effectively displaced the Westminster Standards and rendered elements of historic Christianity as adiaphora (things indifferent). The theological language which held such a union together was essentially liberal and modernist.

It’s worth noting that by “liberalism” Machen was not thinking of the classic liberalism of John Locke and Adam Smith or the political liberalism of more recent vintage. He was thinking of the well-established tradition of theological liberalism which grew up in German soil and was blossoming in the mainline denominations of America in the early part of the twentieth century. From Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that the essence of true religion is a feeling of absolute dependence, to Albert Ritschl (1822–1889), who emphasized the kingdom of God as moral progress, to Adolf von Harnack (1851–1930) who insisted that the development of doctrine marked the abandonment of true Christianity, to Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918) who advocated the social gospel of deeds over creeds, liberalism was its own tradition, with its own heroes, its own core beliefs, and its own ecclesiastical vision. Machen didn’t employ “liberalism” as a theological swear word or a cheap putdown. He understood that liberalism had its own internal cohesion and external aims. He didn’t think liberalism was silly or stupid. He just didn’t think it was Christianity either.

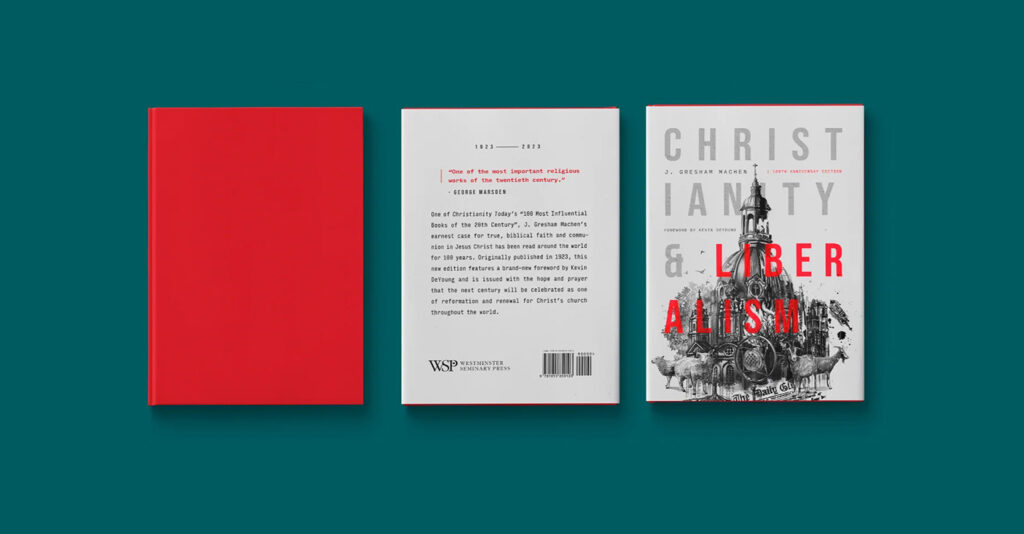

Christianity and Liberalism did not start out as a book. It began as an address, given on November 3, 1921, before the Ruling Elders’ Association of Chester Presbytery, outside of Philadelphia. Perhaps this genesis helps explain why Machen’s book, even today, is so trenchant in expression, so clear in order and articulation, and so accessible to regular Christians. In 1922, the address was published in The Princeton Theological Review. That article was then expanded and augmented with some of Machen’s brief articles from The Presbyterian, a popular magazine at the time, to become the small book published in 1923, whose hundredth anniversary this edition is meant to commemorate.

The bulk of Machen’s book is taken up with the exploration of five essential doctrines of the faith: the doctrine of man, the doctrine of Scripture, the doctrine of Christ, the doctrine of salvation, and the doctrine of the church. In each category, Machen demonstrates that the liberal conception of the faith is fundamentally out of step with historic, biblical Christianity: Where liberalism teaches the goodness of man and the universal fatherhood of God, Christianity insists that Jesus did not come into the world to call the righteous to be better citizens but to save sinners and bring them into the family of God. Where liberalism teaches that true faith is founded on spiritual experience, Christianity insists that true religious experience depends upon the veracity of the historical events in the Bible. Where liberalism lauds Christ as a great teacher and our moral exemplar, Christianity insists that faith in Christ does not make sense apart from a supernatural, sinless, and divine Christ. Where liberalism finds salvation in man’s upward journey to spiritual betterment based on the noble self-sacrifice of Jesus, Christianity proclaims good news based on the propitiatory work of Christ to redeem sinners and save all those who put their faith in him. Where liberalism conceives of the church as a gathering of generally spiritual persons coming together to effect social transformation, Christianity holds forth the church as a group of redeemed men and women (and, for Machen, their children) gathering together to humbly give thanks to Christ for his grace and to find unity in the truth as they worship Christ and him crucified.

Even from this brief overview, we can see that the issues we face today are not all that different from the ones Machen faced one hundred years ago. To be sure, we do not want to engage in Machen-envy and exaggerate our own plight or cast every contemporary disagreement in apocalyptic terms. Thankfully, there are many denominations today which, despite all their struggles, are not questioning the utter sinfulness of man, the authority of the Bible, the full deity of Christ, the substitutionary work of Christ, or the nature of the church as God’s called-out ones. And yet, even if the issues are not exactly the same, the spirit of this century is not unlike the spirit of the last century. There are many lessons we can learn (or re-remember) from Machen’s classic work:

- True unity must be grounded in more than shared mission and shared experience.

- The church must not lose sight of its unique mission in the world, to announce the good news of forgiveness and eternal life in Christ.

- Definitions matter. We must not settle for theological ambiguity.

- It is not enough to say what is true; we must also make clear what is false.

- Beware of all theologies that do not begin with the utter holiness of God and the utter lostness of man.

- We must never stop preaching and singing about the cross—not just as an example of God’s love, but as the place where, in love, God’s Son bore the curse, died in our place, and sustained on our behalf the wrath of God for sin.

- Efforts to “rescue” Christianity from its supposed irrelevance in our day, inevitably make Christianity look outdated and impotent in the days ahead.

The church of Jesus Christ cannot be sustained—and indeed never was founded—on doctrinal indifferentism.

It could be argued that more than anything Christianity and Liberalism is about the doctrine of doctrine itself. If there is one recurring theme throughout the book it is that the church of Jesus Christ cannot be sustained—and indeed never was founded—on doctrinal indifferentism. From the very beginning, Machen argues, the Christian movement was not just a way of life, but a way of life founded upon a message. “It was based, not upon mere feeling, not upon a mere program of work, but upon an account of facts. In other words it was based upon doctrine.” At the root of liberalism is the contention that the way of Christ’s life should not be sullied with over-precise wrangling about the person and work of Christ, or dogmatic insistence upon certain beliefs in order to belong to Christ. While few Christians today care what Harry Emerson Fosdick said a hundred years ago (or have even heard of him), the spirit of his theological latitudinarianism and his insistence on Christianity chiefly as a way of life and a means of cultural reform—these emphases are alive and well in evangelical and Presbyterian churches in America and around the world.

In the end Christianity and Liberalism still matters not only because people need truth but because people need rest. The pulpit that preaches the good news of the cross is proclaiming the only message that can truly bring peace. Ironically, the more the church tries to mimic the world, the less the church has to offer the world. “Is there no place of refreshing where a man can prepare for the battle of life?” Machen asks in the last paragraph of the book. Is there no place where the sunken-down sinner can find grace and gratitude at the foot of the cross? Is there no place where people can be united in the only truths and in the only One who can truly bring divided people together? “If there be such a place,” Machen concludes, “then that is the house of God and that the gate of heaven. And from under the threshold of that house will go forth a river that will revive the weary world.” That’s as true today as it was one hundred years ago.

For more resources, visit the Christianity & Liberalism website.

Purchase a copy of Christianity & Liberalism: 100th Anniversary Edition from our friends at WTS Books.