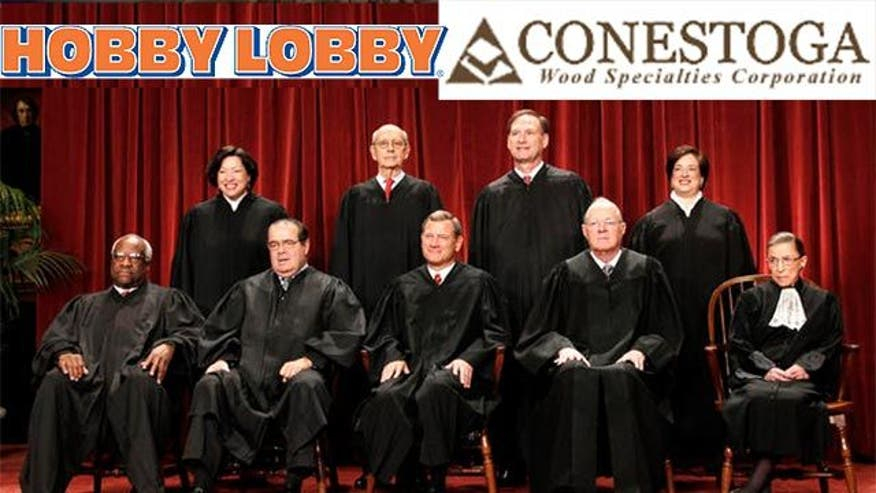

The Hobby Lobby case was not ultimately about abortion or contraception. It was about religious liberty more broadly, and, as far as my untrained legal eyes can tell, about three disputed matters in particular.

Here is a good summary of the issues as presented in the Amicus brief filed by Michigan, Ohio and eighteen other states in support of Hobby Lobby, Conestoga, and Mardel:

The threshold question here is whether for-profit, secular businesses may exercise religion and therefore fall within the religious liberty protections of RFRA [Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed unanimously by the House, 97-3 by the Senate, and signed by President Clinton in 1993]. It is a question that is basic to American democracy. Its answer requires this Court to return to first principles. And the answer is a simple one.

Americans may form a corporation for profit and at the same time adhere to religious principles in their business operation. This is true whether it is the Hahns or Greens operating their businesses based on their Christian principles, a Jewish-owned deli that does not sell non-kosher foods, or a Muslim-owned financial brokerage that will not lend money for interest. The idea is as American as apple pie. And RFRA guarantees that federal regulation may not substantially burden the free exercise of religion absent a compelling governmental interest advanced through the least restrictive means.

Any contrary conclusion creates an untenable divide between for-profit and non-profit corporations. All sides admit that RFRA extends its protections beyond individuals to at least some corporations. Despite assumptions made by certain of the judges below, nothing in the relevant state laws restricts corporate endeavors to the sole purpose of maximizing revenue at all cost. There is and should be no general federal common law of corporations. And nothing in RFRA limits its application to administratively certified religious entities.

The argument put forward by the United States is predicated on a view that seeking profit changes everything. Not so. The Hahns and the Greens, as do others, seek to operate their family-owned businesses according to religious principles. That they seek also to earn a profit does not nullify or discredit their beliefs. The federal courts cannot rewrite state law on corporations somehow to change this reality.

The Mandate also imposes a substantial burden on these family-owned businesses. Conestoga, Hobby Lobby, and Mardel are guided by religious principles affirming the inviolability of human life, and no one questions the sincerity of those beliefs in these cases. Courts should not become enmeshed in evaluating the interpretive merits or proper doctrinal weight of religious principles. Their religious propriety is not for the courts to second guess. And the government lacks a compelling interest justifying the substantial burden it seeks to impose when the businesses adhere to these guiding religious principles. The Affordable Care Act includes several sweeping exceptions. The claim that the Mandate must be applied to entities with a sincere religious objection is belied by the fact that it already excludes tens of millions of plan participants.

Government directives cannot confine religious liberty to the sanctuary or sacristy. Such a truncated view of religion threatens to create a barren public square, empty of the religious beliefs of ordinary Americans. This is an important principle, and it protects all persons.

So what does all that mean? There are three crucial points:

1. Individuals do not relinquish their First Amendment rights when they associate together in a for-profit business.

2. The healthcare Mandate imposed a “substantial burden” on the businesses in question.

3. Any compelling interest the government may have in providing contraceptives was not “advanced through the least restrictive means.”

That last point is especially important. When religious persons wax eloquent about the inviolable liberty of conscience, the quick rejoinder is “Yeah, but what if your conscience doesn’t allow you to cover blood transfusions or your religious conscience tells you it’s okay to discriminate against ethnic minorities?” Point taken. The appeal to conscience is not a right to unchecked liberty at any cost. Religious freedom does not mean we are free to do whatever we want. The government will sometimes burden the free exercise of religion, but, according to RFRA, only if it has a compelling interest to do so and advances this interest through the least restrictive means.

In the end, the Court decided in favor of Hobby Lobby on the three crucial points listed above:

We hold that the regulations that impose this obligation violate RFRA, which prohibits the Federal Government from taking any action that substantially burdens the exercise of religion unless that action constitutes the least restrictive means of serving a compelling government interest.

In holding that the HHS mandate is unlawful, we reject HHS’s argument that the owners of the companies forfeited all RFRA protection when they decided to organize their businesses as corporations rather than sole proprietorships or general partnerships. The plain terms of RFRA make it perfectly clear that Congress did not discriminate in this way against men and women who wish to run their businesses as for-profit corporations in the manner required by their religious beliefs.

Since RFRA applies in these cases, we must decide whether the challenged HHS regulations substantially burden the exercise of religion, and we hold that they do. The owners of the businesses have religious objections to abortion, and according to their religious beliefs the four contraceptive methods at issue are abortifacients. If the owners comply with the HHS mandate, they believe they will be facilitating abortions, and if they do not comply, they will pay a very heavy price—as much as $1.3 million per day, or about $475 million per year, in the case of one of the companies. If these consequences do not amount to a substantial burden, it is hard to see what would.

The free exercise of religion and liberty of conscience are God-given rights. We would surely miss them more than we know if they were done away with. We can give thanks that today, when they could have easily been undermined, they were instead upheld.