I hope you’ll put on your thinking caps and practice a little patience as I try to connect the world of my doctoral studies with the world of our contemporary blog disputes.

For the four of five of you who are left, I want to introduce you to John Witherspoon’s Essay on the Connection Between the Doctrine of Justification by the Imputed Righteousness of Christ, and Holiness of Life.

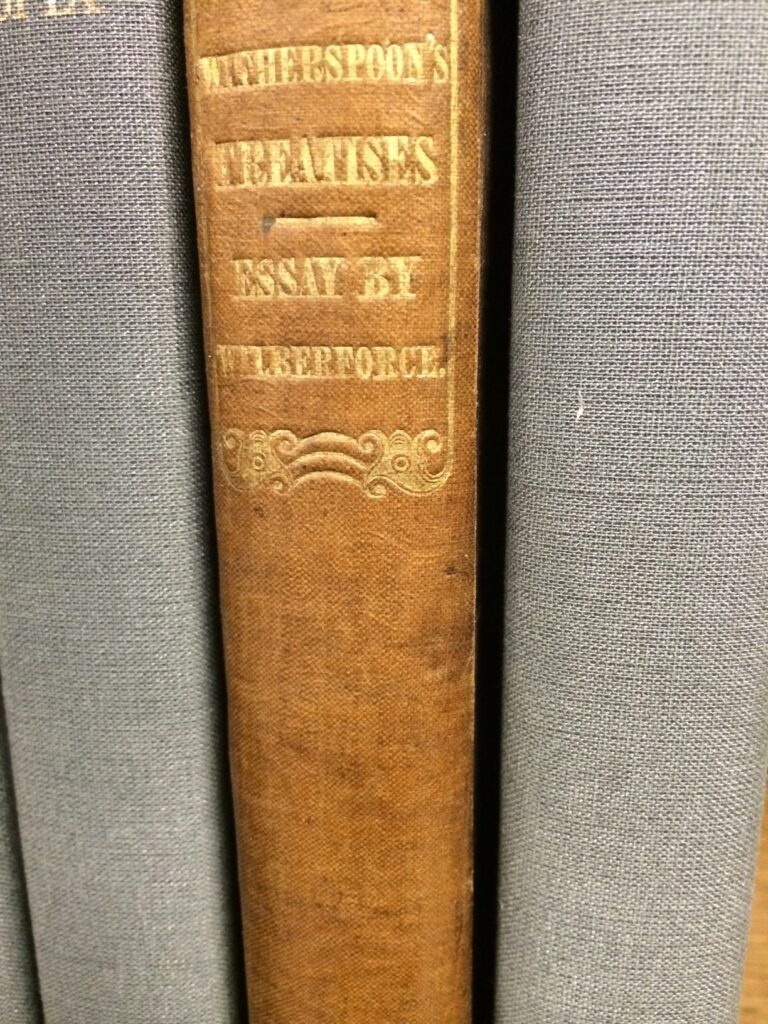

First published in 1756, the short book which began as two sermons would go through three editions in the next twelve months. In 1764, the essay was published again, this time with a new and longer piece from Witherspoon, A Treatise on Regeneration. These two treatises would be reprinted together numerous times over the next fifty years, including an 1830 edition with an introduction by William Wilberforce in which he commends the two Witherspoon essays, noting that their “excellence” was “far too well established to render necessary any eulogium of mine.”

Although largely forgotten now, Witherspoon’s Essay on Justification was much beloved in a previous century.

Putting Things in Context

Prefixed to the Essay on Justification is a letter to Rev. James Hervey, an Anglican Rector in Northamptonshire and a friend of Witherspoon’s. In the prior year (1755), Hervey published his magnum opus, Theron and Aspasio, a ponderously titled, massive three-volume work which, through a series of dialogues between two men (Theron and Aspasio) promoted and defended a strongly Reformed understanding of justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ.

Years earlier, before becoming a Calvinist, Hervey had been a part of the Holy Club at Oxford and was mentored by John Wesley. Until the publishing of Theron and Aspasio, Hervey and Wesley were close. After 1755, not so much. Before Theron and Aspasio went to press, Hervey had sent a draft of the work to Wesley asking for his comments. Wesley offered several criticisms. Hervey, it seems, did not change the manuscript (perhaps he was only looking for stylistic help, not doctrinal correction). After publication, Wesley continued to write Hervey, and Hervey continued to ignore his mentor’s advice. Finally in 1758, Wesley published his last and longest letter to Hervey, a tedious point-by-point rebuttal of specific lines quoted “chapter and verse” from Theron and Aspasio. Sadly, Hervey died on Christmas day 1758, still fretting over a response to Wesley.

Wesley’s main objection to Theron and Aspasio was that it taught justification by imputed righteousness, a doctrine Wesley considered an obvious recipe for antinomianism. It’s reasonable to think that even before the book was published in 1755, and certainly before Witherspoon’s essay came out in 1756, both Hervey and Witherspoon were aware of Wesley’s disdain for imputation and his fears of antinomianism. And Wesley wasn’t alone. Jonathan Edward’s pupil, Joseph Bellamy–on different grounds, but also related to the charge of antinomianism–would lambast Hervey in the years head. Theron and Aspasio caused quite a stir. It was loved by some and hated by others.

Which is why Witherspoon’s dedicatory letter to James Hervey is significant. It was, according to Witherspoon, “a public declaration of my espousing the same sentiments as to the terms of our acceptance with God.” The Scotsman was coming to the defense of his English friend. Witherspoon acknowledges in the letter to Hervey that the “most plausible” and “most frequently” made objection against imputation is that “it loosens the obligations to practice.” Whether Witherspoon thought the critics were entirely unfair or whether he thought Hervey had left himself vulnerable to the charge of antinomianism is unclear. What is clear is that Witherspoon wrote his Essay on Justification to stand in the gap and answer the objections that Wesley and others were raising against a Reformed doctrine of justification.

A Little Bit of History Goes a Long Way

One of the great things about studying history is that it can illuminate the present. The debates of the eighteenth century are not identical with our debates. We cannot substitute our good guys (whomever they may be) with their good guys (on whichever side) and read the events of their day like a fable for our day. On the other hand, the same theological issues come up over and over again.

What’s particularly instructive about Witherspoon’s essay is how:

- He was coming to the defense of a robust understanding of justification and imputation.

- Yet, he was concerned that the doctrine not be misunderstood.

- He was passionate about justification and holiness of life.

- He saw justification connected to sanctification not in just one way, but in many ways.

- He wanted to avoid extremes. Even in the midst of controversy, he tries to be balanced, nuanced, and careful.

How Justification and Sanctification Are Connected

The central concern for Witherspoon is to answer the objection that says “the obligation to holiness of life” is weakened “by making our justification before God depend entirely upon the righteousness and merit of another” (Works, 1:46). He feels the need to defend the doctrine of justification because it is too often despised by enemies and promoted poorly by friends. Among this latter group, he sees two kinds of errors.

Some speak in such a manner as to confirm and harden enemies in their opposition to it: they use rash and uncautious expressions. . . .in the heat of their zeal against the self-righteous legalists seem to state themselves as enemies, in every respect, to the law of God, which is just and good. (1:48)

That’s one mistake: being so intent on routing the legalists that you run off the law altogether. The other danger is to so safeguard the doctrine of justification that no one ever feels scandalized by it.

Other, on the contrary, defend it in such a manner as to destroy the doctrine itself, and give interpretations to the word of God, as if they were and known to be so, the objection would never have been made because they would not have been so much as an occasion given to it. (1:48).

In other words, some friends of justification are so scared of legalism they end up with no place for the law, while others are so scared of antinomianism they do nothing to alarm the legalists.

After the introduction, the bulk of Witherspoon’s essay consists of six reasons the doctrine of justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ strengthens rather than weakens our obligation to holiness.

1. “In the first place, he who expects justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ hath the clearest and strongest conviction of the obligation of the holy law of God upon every reasonable creature, and of its extent and purity” (1:52). For the imputation of Christ’s obedience to be necessary, there must be an obligation to obedience upon everyone made in the image of God. The law is shown to be good and holy by the act of imputation itself.

2. “In the second place, he who believes in Christ and expects justification through his imputed righteousness, must have the deepest and strongest sense of the evil of sin in itself” (1:55). If sin were not so heinous, so to be feared, so to be avoided, so be killed, there would have been no need to Christ’s propitiatory sacrifice to turn away the wrath of God.

3. “In the third place, he who expects justification only through the imputed righteousness of Christ, has the most awful views of the danger of sin” (1:60). Witherspoon is aware that “many readers” will consider this point about the danger of sin to be “improper” based on the believer’s new status in Christ. Fear, he anticipates some to object, can have no place as a motivation for Christian obedience. But elsewhere, Witherspoon distinguishes between filial fear and slavish fear (1:134). We do not fear God as judge, but we ought to fear displeasing him as our Father. Because we need to be justified through the atoning death of Christ, we can see sin in all its awfulness. Witherspoon, therefore, rejects as “un-guarded and anti-scriptural” notions that we are “justified from all eternity” or that “God doth not see sin in a believer” or that “afflictions are not punishments, and other things of like nature” (1:60-61).

4. “In the fourth place, those who expect justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ have the highest sense of the purity and holiness of the divine nature” (1:63). Our need for a redeemer and for the righteousness of another ought to impress upon us the holiness of the God we serve and are to emulate.

5. “In the fifth place, those who expect justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ must be induced to obedience in the strongest manner by the liberal and ingenuous motive of gratitude and thankfulness to God” (1:66). This is where our discussion often starts and stops. But for Witherspoon, gratitude is only one of many ways in which justification spurs us on to a life of holiness.

6. “This leads me to observe in the sixth and last place, that those who expect justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ must be possessed of a supreme or superlative love to God which is not only the source and principle, but the very sum and substance, nay, the perfection of holiness” (1:70). Or to put it more succinctly, “love is the most powerful means of begetting love.” The love of God is what compels us to be holy, entices us to be holy, and what is meant by being holy.

A Final Thought (In Two Parts)

After finishing the main body of his argument, Witherspoon offers one last “general observation.” He fears that diligence in personal holiness is to easily undermined by “despair of success,” and so he concludes with two gospel encouragements (1:77).

First, we ought to have hope of acceptance with Christ (1:78). We are sinners. We will sin. We still need a Savior. So let us not despair that Christ will forgive us when we sin.

Second, we can have “diligence in duty” because the Holy Spirit will lead us and guide us in all duty (1:79). We are saved by grace and will be sanctified by grace. Therefore, we should not despair: Christ will be there when we fail and the Spirit will help us to succeed. Witherspoon loves the doctrine of “redemption by free grace” because in all aspects it “gives less to man and more to God than any other plan” (1:81). It is meant to cut our hearts and kill our pride.

And so Witherspoon concludes with a strong exhortation to keep preaching this good news. The best defense of justification by imputation is “zealous assiduous preaching the great and fundamental truths of the gospel, the lost condemned state of man by nature, and the necessity of pardon through the righteousness [of Christ], and the renovation by the Spirit of Christ” (1:91). What the world needs in its sin, and the church in all its weakness, is for this “everlasting gospel” to be preached in all its purity and simplicity (1:92).

Sounds good to me.