We should attempt great things while enduring great hardships

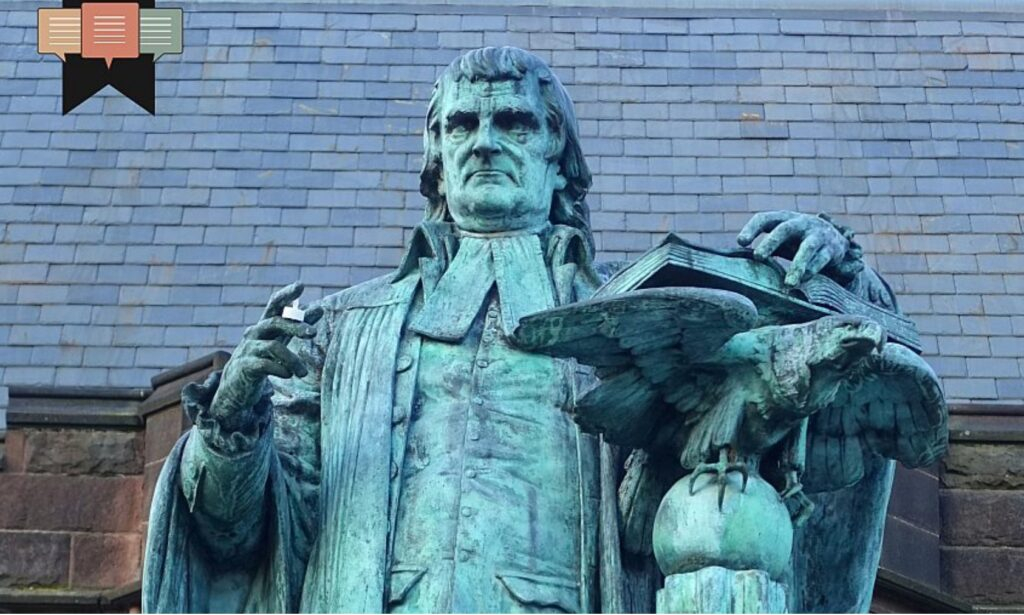

John Witherspoon was the president of Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey) from 1768, when he arrived from his native Scotland after a career in pastoral ministry, until he died in 1794. Twice during his presidency—in 1775 and again in 1787—Witherspoon preached a message before commencement on a theme we don’t hear a lot about today. “My single purpose from these words at this time,” he told his students, “is to explain and recommend magnanimity as a Christian virtue.” In a day when presidents (from both parties) have been known to berate their opponents with foul language, in a cultural context where courage is often in short supply, and in an online world where offendedness is promoted next to godliness, we could all use a fresh exhortation to magnanimity.

The title of this article calls magnanimity a “manly virtue.” By that, I don’t mean that magnanimity is unique to men or that women are not also called to this trait. After all, Witherspoon calls it a Christian virtue. But I do think magnanimity is a virtue particularly befitting to manhood, and that manhood bereft of magnanimity is especially lamentable. When the Apostle Paul enjoined the Corinthians to be strong, to stand firm in the faith, and to “act like men” (1 Corinthians 16:13), he was calling men and women to courage, but he was also embracing the notion that fortitude in the face of opposition is what we associate with manliness.

According to Witherspoon, magnanimity entails five commitments: (1) attempting great and difficult things, (2) aspiring after great and valuable possessions, (3) facing dangers with resolution, (4) struggling against difficulties with perseverance, and (5) bearing sufferings with fortitude and patience. In short, the magnanimous Christian is eager to attempt great things and willing to endure great hardships.

Witherspoon took for granted that the world approves of magnanimity. His concern was that some might conclude that calling men (like his Princeton graduates) to strength and valor and ambition does not fit with the tenor of the gospel. Even today, if you hear the word “masculinity” at all, it is likely to come after the word “toxic.” Christians have often struggled to know how godliness and manliness mesh. But virtues, Witherspoon insisted, can never be inconsistent with each other. He noted that while the gospel would have us mourn for our sin and cultivate a humility of spirit, we are also “called to live and act for the glory of God and the good of others.” This means that the truly pious man, in striving for greatness, will seek to gain possessions more valuable than earthly riches. “The glorious object of the Christian’s ambition is the inheritance incorruptible and undefiled, and that fadeth not away,” Witherspoon preached to his students.

The magnanimous person does not bear grudges, does not wallow in self-pity, does not demand penance, and does not stoop to settle every score.

Christianity is not opposed to ambition, but ambition will look different for the Christian. “Everyone must acknowledge,” Witherspoon said, “that ostentation and love of praise, and whatever is contrary to the self-denial of the gospel, tarnish the beauty of the greatest actions.” True greatness does not lie in self-promotion, endless bravado, and passing along our own praise. Likewise, manliness does not mean we must be larger than life gunslingers and gladiators who swagger into town ready to kill or be killed. There is more than one way to be brave and many ways to be strong. Not everyone will be gifted with brains or brawn. Not everyone will have the opportunity for world-altering heroism. “But,” Witherspoon noted, “that magnanimity which is the fruit of true religion, being indeed the product of divine grace, is a virtue of the heart and may be attained by persons of mean talents and narrow possessions and in the very lowest stations of human life.”

If magnanimity calls us to attempt great things, it also compels us to endure great suffering. Merriam-Webster defines magnanimity as “loftiness of spirit enabling one to bear trouble calmly, to disdain meanness and pettiness, and to display a noble generosity.” Would that this describe our political leaders, our intellectual leaders, and Christian men more generally. While we all should disdain pettiness, there is something particularly discomfiting when a man feels the need to advertise the offenses against him and swing at every offender. The magnanimous person does not bear grudges, does not wallow in self-pity, does not demand penance, and does not stoop to settle every score.

In the end, the two parts of magnanimity are inseparable, for the great man is measured not only by what he does but by what he does not do. We would do well to be more like David pardoning Shimei than the sons of Zeruiah looking for the next enemy to execute. Bearing burdens, eschewing meanness, and setting an example of noble generosity is not just a saner and more effective way to live; it is the way of the cross. For the manly virtue of magnanimity is the way of the One who accomplished great things by defeating His foes, even while crying out, “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.”