First off, my usual disclaimer and explanation.

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of good books published in 2019. There are plenty of worthy titles that I am not able to read (and lots I never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year. “Best” doesn’t mean I agreed with everything in them; it means I found these books—all published in 2019—a strong combination of thoughtful, useful, interesting, helpful, insightful, and challenging.

10. Robert Louis Wilken. Liberty in the Things of God: The Christian Origins of Religious Freedom (Yale University Press). There have been plenty of books in recent years about current threats to religious freedom. This book is a look at the history of the idea. In particular, Wilken argues “religious freedom took form through the intellectual labors of men and women of faith who sought the liberty to love and serve God faithfully in the public square” (5-6). In other words, religious freedom was not a Christian capitulation to pluralism or Enlightenment philosophy, but a Christian idea in its own right.

9. Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones (eds). Making Evangelical History: Faith, Scholarship and the Evangelical Past (Routledge). If there is a theme that holds these chapters together it’s the tension between history that inspires the faithful and history that is faithful to the nuances, imperfections, and ambiguities of the past. I don’t believe the editors mean for Christians to choose between spiritual inspiration and intellectual rigor as mutually exclusive priorities, but they do mean to highlight how evangelical histories have typically aimed at the former more than the latter. For my part, I agree with Atherstone’s insistence that evangelicals ought to embrace both the “confessional” and also “professional” approaches to history (11).

8. Douglas Murray. The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race, and Identity (Bloomsbury). The fact that Murray is a gay atheist helps and hurts the book. On the one hand, it’s nice to see Murray sympathize with conservative Christianity and make the sorts of points many Christians would make. On the other hand, there is no doubt Murray is missing out on all sorts of resources and ideas for understanding human nature, sex, and forgiveness. Murray is at his best when he argues that our Western culture is asking for impossibilities. We must believe that women have a right to be sexy without being sexualized, that race doesn’t exist and that race defines everything, that Caitlyn Jenner is a woman but Rachel Dolezal is not black. His argument that people are much less oppressed than they think is bound to be controversial. But he makes a good point that the more comfortable most people are, the more suffering carries rhetorical (and real) power.

7. Cal Newport. Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (Portfolio). After reading Newport’s earlier book on Deep Work, I was eager to get this follow-up volume on reducing digital distraction. Newport wisely observes that we are succumbing to screens not because we are lazy (though that may play a part), but because billions of dollars have been invested to push us into digital addiction. The call for digital minimalism, therefore, is not about efficiency or usefulness, but about autonomy. Like Newport’s book on work, I find this one easier to agree with than to put into practice.

6. Robert Caro. Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Knopf). Fascinating from start to finish. I confess I have not read all of Caro’s famous work on LBJ, but I have read enough to know that as a researcher and political biographer, he has no equal. This little book is a snapshot into the subjects of his big biographies—Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson—as well as a glimpse into the method behind Caro’s own brilliant madness.

5. Stephen Witmer. A Big Gospel in Small Places: Why Ministry in Forgotten Communities Matter (IVP). A wonderful antidote to one of the last remaining prejudices: small towns are not strategic, and small-town folks are rednecks and rubes. With a good mix of theology, exegesis, cultural analysis, and personal reflections, Witmer manages to be warmly pro-small places without ever sounding anti-big cities. This book will encourage many and may be used by God to call good gospel ministers back into our forgotten communities.

4. Kevin G. Harney. No Is a Beautiful Word: Hope and Help for the Overcommitted and (Occasionally) Exhausted (Zondervan). With 54 short chapters about saying “No,” you don’t have to wonder what the book’s big idea is all about. Nothing revolutionary, but lots of good illustrations, practical advice, and spine-stiffening courage for saying “No” to most things, so we can say “Yes” to the best things. A necessary book for anyone who feels margin-less, overstretched, and crazy busy.

3. Carl H. Esbeck and Jonathan J. Den Hartog (eds). Disestablishment and Religious Dissent: Church-State Relations in the New American States 1776-1833 (University of Missouri Press). I know, the title screams “Take me to the beach!” But this really is a fascinating book. Each of the original 13 colonies, plus a few other early states, is given its own chapter. From New Jersey (the first and simplest case of disestablishment) to Massachusetts (the last and most complicated) a talented group of scholars detail the political, cultural, and legal process of disestablishment in early America.

2. Robert Letham. Systematic Theology (Crossway). The Reformed world has been blessed with a steady stream of new systematic texts and resources in the past decade. What makes Letham’s stand out is his knowledge of the entire tradition, from the Fathers to the Reformers to contemporary voices. Letham marshals his impressive knowledge in one volume that is clearly organized and written without a lot of technical jargon. This is a book I will consult for years to come.

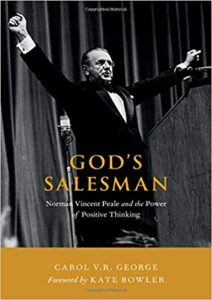

1. Carol V. R. George. God’s Salesman: Norman Vincent Peale and the Power of Positive Thinking (Oxford University Press). Originally published in 1993 and then reissued in a second edition this year (no doubt, because of President Trump’s connections to the Marble Collegiate minister), a biography of Norman Vincent Peale may seem an odd choice for my top 10 list. I don’t agree with Peale’s methodology, priorities, preaching, or theology. But he’s probably the most important 20th-century American religious leader that few think of. Even with something of a Reformed resurgence in recent decades, the reality is that the most popular Christian books, churches, and preachers in this country are still much more like Peale than like Piper. From his trust in the basic goodness of the human mind and heart, to his valuing of experiential and personal faith over doctrine and traditional religion, to his lifelong passion for Republican politics, to his emphasis on health, achievement, and success, Peale not only embodied the spirit of his age, his blending of New Thought philosophy and neo-evangelical ethos also helped shape generations to come.