In 2021 I attempted an analysis of “Why Reformed Evangelicalism Has Splintered,” arguing that many of the old networks and alliances had fallen apart and that four new “teams” had emerged. I labeled these “teams” (or “impulses” or “instincts”) with four positive terms: (1) contrite, (2) compassionate, (3) careful, and (4) courageous. Each label indicates what that “team” considers to be the need of the hour. The 1s want the church to acknowledge its own sins and failures; the 2s want the church to deal lovingly and winsomely with others (especially with outsiders); the 3s want the church to be theologically rigorous and intellectually precise; the 4s want the church to be bold and aggressive in opposing the anti-Christian spirit of the age. While some of the specific cultural and political issues I highlighted have receded to the background, and others have come to the foreground, I think the analysis is still accurate.

The purpose of my 2021 article wasn’t to argue for a particular position. I wanted to describe each “team” in a way that they might recognize. As I said in the article,

Although I’m closer to 3 than to any other category, I’ve tried my best to label each group in a way that expresses the good that they are after. Most of us will read the list above and think, “I like all four words. At the right time, in the right place, in the right way, the church should be contrite, compassionate, careful, and courageous.”

Big picture categorizations lose their effectiveness if people sense you are setting up strawmen so that your “team” can win the day.

What I want to do in this article, now three years later, is let my affinity for the 3s show through and make the case for being careful. I’m not waving the banner for Team Careful because I think contrition, compassion, and courage are unimportant. I don’t mean to suggest that the 3s are all right and the 1s, 2s, and 4s are all wrong. In fact, I will insist that contrition, compassion, and courage are essential to faithful Christian witness. I do want to argue, however, that these three impulses will veer off track unless they are shaped and governed by theological, intellectual, and verbal carefulness. Carefulness is not more important than the rest, but it is the one category without which the other three categories will not be helpful and cannot be perfected.

Four Categories and Four Cardinal Virtues

At this point you may be wondering why the title of this article is “In Praise of Prudence” instead of “The Case for Being Careful.” The reason: I want to argue for carefulness by making an appeal to prudence, the latter being a richer and deeper category than the former.

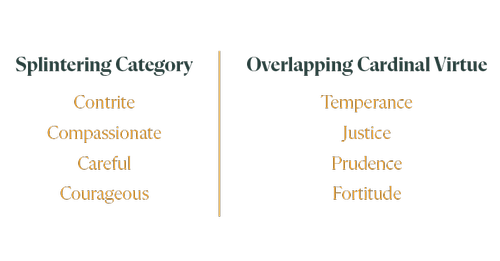

About two years after I wrote the splintering article, I read Josef Pieper’s book on The Four Cardinal Virtues. In his classic treatment of the topic, Pieper (a distinguished twentieth-century German Catholic philosopher) draws from the Christian tradition, and from Thomas Aquinas in particular, in exploring the meaning and importance of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Sometime after finishing the book, it occurred to me that the four cardinal virtues map fairly well onto the four categories in my article. The mapping is not a perfect match (especially in two categories), but it’s close. The contrite position overlaps with temperance, compassion moves in the same direction as justice, carefulness is akin to prudence, and courage bears a close resemblance to fortitude.

Let’s look at each virtue in turn, saving prudence for the end. All quotations are from the University of Notre Dame English translation (1966) of Pieper’s book.

Temperance

One might think that “contrite” would match up with “justice,” given that those at the left end of the spectrum seem most concerned with “social justice” issues. But temperance is a better fit. When considering the virtue of temperance, don’t think of moderation or of mere emotional tranquility. Think more comprehensively of the right ordering of our inner lives. If prudence is directed toward existent reality, and justice to our fellow man, temperance “refers exclusively to the active man himself” (147). To be sure, temperance is often connected to sexual behavior and calls forth the duties of virginity and chastity. But temperance cannot be reduced to sexual ethics. At its core, temperance is about self-denial and selflessness. “Whatever forces of self-preservation, self-assertion, self-fulfillment, destroy the structure of man’s inner being, the discipline of temperance and the license of intemperance enter into play” (150).

The connection with contrition is that temperance insists upon humility, gentleness, and meekness—qualities that Team Contrite faults the church for lacking in spades. If I can preview an insight from prudence here, one of the problems with the 1s is that they are much quicker to enjoin their ideological opponents to be contrite than they are apt to lament the temptations and failings of their own class and their own networks. But that doesn’t mean their criticisms are entirely without merit. Christians do get intoxicated with power; churches do get mired in scandal. At its best, Team Contrite is calling the church to be the best version of itself, to be (in Pieper’s language) full of “chastity, continence, humility, gentleness, [and] mildness” and to drive out “unchastity, incontinence, pride, [and] uninhibited wrath” (151).

Justice

“Justice is the virtue which enables man to give to each one what is his due” (44). Drawing on Aquinas, Pieper stresses that justice has to do with debts, what someone owes to someone else (57). We are debtors to God, debtors to parents, debtors to our country (108). Justice is the highest of the three moral virtues (temperance, justice, fortitude) because what we do to others visibly reveals the invisible contours of the heart.

Linking Team Compassion to the virtue of justice may seem like a stretch. Compassion is usually thought of as being an expression of mercy, not of indebtedness. The connection is that compassion, like justice, focuses on our neighbors. Temperance and fortitude are directed toward the self; prudence is directed toward the reality of the outer world; of the cardinal virtues, only justice is directed toward others (54). The compassion instinct often leads to explicit concerns over injustice. If the 1s are likely to rebuke the church for injustice, the 2s are more likely to call for sympathy and lament. The other-directed instinct also prompts Team Compassion to think about how unpopular biblical truths can be presented in ways that are most palatable, especially for those who are well-educated and anti-religious.

Fortitude

When looking at the four cardinal virtues and my four splintering categories, fortitude and courage have the most obvious overlap. Fortitude is a readiness to fall—to die if necessary—in battle (117). The courageous person accepts insecurity; he is willing to take risks for what is right. The goal is not to suffer injury for its own sake. Martyrs in the early church were forbidden from reporting themselves to the magistrates. One can be too ready to fall in battle. Bravery is a means to an end. Fortitude is virtuous not because it is willing to destroy the enemy, but because it means to preserve, acquire, or defend “a deeper, more essential intactness” (119).

This is an important point. When we think of courage or bravery, we usually think of charging into battle to fight against the bad guys, no matter the odds and no matter the cost. To be sure, this can be an expression of fortitude. But just as often, courage means pressing on in quiet consistency when no one is looking. “Endurance is more of the essence of fortitude than attack” (128). Far from passive resignation, endurance represents a strong activity of the soul, a vigorous clinging to what is good. Fortitude will not allow for a timid Christianity, but neither does it demand an existence that is “activistically heroic” (128).

Prudence

To our ears, prudence seems a rather lame virtue. I can’t help but think of Dana Carvey’s impression of George H. W. Bush saying in a wimpy, nasally twang, “Wouldn’t be prudent.” Fortitude and justice sound strong; prudence sounds like a weak refusal to take any risks. Prudence “carries the connotation of timorous, small-minded, self-preservation, of a rather selfish concern about oneself” (4). Just as “carefulness” can appear to be the least noble of my four categories, prudence strikes us as a cautious, calculating, evasive pseudo-virtue.

But this kind of cynical squint misses what prudence is about and why it is so centrally important. The prudent person is not a mere tactician or proceduralist. The prudent man possesses an accurate assessment of the world around him. “Prudence implies the kind of objectivity that lets itself be determined by reality, by insight into the facts. He is prudent who can listen in silence, who can take advice so as to gain a more precise, clear, and complete knowledge of the facts” (92). To be prudent is to be committed to reality before feeling, to reason before experience, and to truth before action.

The Mold and Mother of Virtue

There is no single cardinal virtue that is more important than the others. All four stand or fall together. But if there is no ranking in terms of importance, there is a ranking in terms of logical priority. And in this ranking, prudence comes first. “No dictum of traditional Christian doctrine strikes such a note of strangeness to the ears of contemporaries, even contemporary Christians, as this one: the virtue of prudence is the mold and ‘mother’ of all the other cardinal virtues, of justice, fortitude, and temperance” (3). The good man is good only in so far as he possesses prudence. Being precedes Truth, and Truth precedes the Good (4).

Therefore, we cannot do what is good unless we act out of and according to what is true as defined by the God who created all things and rules over all. “In other words, none but the prudent man can be just, brave, and temperate” (3).Prudence is unique among the cardinal virtues. If the other three are technically the “moral virtues,” then prudence is what guides the moral life. As we have already seen, prudence is neither directed toward the self (like fortitude and temperance), nor toward others (like justice), but toward concrete reality.

Prudence is the virtue of seeing things as they really are, and we can only do what is right if we know what things are like. Far from consigning us to cowardly inaction, prudence leads us to act according to truth and with clear-eyed objectivity (10).

The danger with prudence, like the danger with carefulness, is that it can devolve into intellectualism, nitpicking, and self-centered caution. Each of my four categories can be lived out in the wrong way. It is possible for me and my fellow 3s to give very careful analysis on very complicated issues without ever doing much of anything besides giving careful analysis. Prudence cannot be a virtue on its own. Prudence is only virtuous in so far as it leads to justice, fortitude, and temperance. But if prudence is not virtuous by itself, neither can justice, fortitude, and temperance be virtuous apart from prudence. Prudence is the cause of the other virtues, the measure of the other virtues, and the quality that informs the other virtues (6-7).

When the contrite rail on the sins of the church by projecting their own experiences on others, or when they impute to the church everywhere the sins of the church in a few places, they are not acting according to prudence.

When the compassionate speak out against injustice without determining whether injustice has taken place, or when they build bridges with only one kind of person (and never think to build walls), they are not acting according to prudence.

When the courageous confuse an eagerness to attack with the virtue of fortitude, or when they denounce the moral rot of our day with the weapons of the world or without describing their opponents fairly, they are not acting according to prudence.

If this sounds hyperbolic—like exaggerated flag-waving from the captain of Team Careful—consider that prudence is, in essence, another word for ethical maturity, a call for that wisdom and character without which the moral life is not possible (31).

Conclusion

The “case for being careful” is that prudence must be preeminent among the four cardinal virtues. We cannot educate a person in justice, fortitude, and temperance without first educating him in prudence (31). That is to say, we must know what things are really like. We must grasp concrete reality. We must be objective. We must be accurate and precise with our words. We must be guided—before personal hurt or personal experience, even before the noble hope of influencing people with the gospel or the honorable goal of holding back the forces of evil—by what is true.

“Man can have no other standard and signpost than things as they are and the truth which makes manifest things as they are; and there can be no higher standard than the God who is and His truth” (40). If Jesus is right, and surely he is, that we are sanctified by the truth (John 17:19), then there is no path to faithful Christian obedience and faithful cultural witness that does not begin in praise of prudence.

Kevin DeYoung is the senior pastor at Christ Covenant Church (PCA) in Matthews, North Carolina and associate professor of systematic theology at Reformed Theological Seminary.